Elevating the ordinary with focus stacking

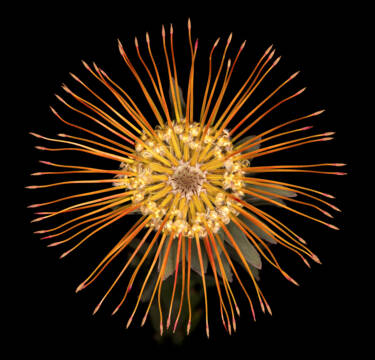

Think you know everything there is to know about focus? Welcome to focus stacking, the art of creating close-ups packed with the kind of intricate detail standard zoom just can’t capture

Focus stacking is a technique that produces close-up images of depth and detail beyond that seen in conventional close-ups. If you’re not familiar with the technique, you might be wondering: what’s the point? Why not just adjust your lens to f/11, f/16 or f/22 to get the depth you need?

It’s a good question, with an easy answer: focus stacking results in the kind of striking photographs you see here. To create them, award-winning fine-art photographer David Leaser took multiple images of his floral subjects at different focus points. Then, using software, he layered the separate photographs to create a stunningly sharp, detailed composite image. Focus stacking, therefore, extends depth-of-field in macro photography by layering separate photographs of different focus points into a single image.

In this tutorial, David will help you get to grips with the equipment and techniques you need to become a focus stacking pro…

David Leaser

Trial, error, results

More than a decade ago, David was working on a series in the Amazon when he developed an obsession with the smallest living things in the rainforest, including its most minute flowers.

He soon realised that even the very best macro lenses couldn’t achieve the detail and the depth of field he was after. He began experimenting with focus stacking in a bid to capture and share a ‘bee’s-eye view of nature.’

He started by putting his then Nikon D3X with the Nikon AF-S Micro NIKKOR 60mm f/2.8G ED lens on a motorised slider. This set-up moved the camera and lens closer and closer to the subject at preset intervals, taking several photographs every time, capturing a different focus point in each image.

In this feature, David uses his Nikon D850, with its built-in focus shift means the camera itself stays perfectly still, but, of course, you can use a Z mirrorless camera, too.

The Nikon Z 6, Z 7, Z 7II and Z 8 and Z 9 hybrid cameras come with focus shift shooting, a menu function that allows you to set conditions for a series of images to be stacked in editing software.

Versus David’s old slider system, using the D850 or mirrorless camera means fewer moving parts, less fiddling with settings, and less equipment to carry when shooting outside. Plus, no slider means no need for an extra power supply or batteries.

In fact, the results are better. Rotating the lens instead of moving the camera cuts down on (or cuts out) a major issue that you usually need stacking software to address: parallax. This is where what you see in the viewfinder is very different to what your camera captures. The effect gets worse the closer you get to your subject.

The D850 captures all the photographs to be layered into the final image almost automatically, but there’s more to the process than clever tech. There’s equipment to be set up, settings to be tweaked and test shots to snap, too. According to David, this is where the real creativity comes in.

If you’re interested in taking your own focus shots or simplifying your slider process, follow David’s step-by-step guide to effortless focus stacking...

Set-up

David uses an AF-S Micro NIKKOR 60mm f/2.8G ED lens on his D850. Plus, a sturdy tripod (a Manfrotto 3251), small LED clamp lamp, backdrop (he used black velvet for the photos in this article) and stacking software (David likes Zerene Stacker).

And then there’s his secret weapon. Take a look at the photos in this article, and you’ll see that the single most important factor is light. Or, rather, light control.

Nikon’s wireless Speedlight system is designed for close-ups, and gives you complete control over your lighting. It comes in two versions: the R1 (two SB-R200 Speedlights, a mounting ring and a selection of lens adaptors the ring can fit to), and the R1C1 (two SB-R200 Speedlights, the SU-800 commander, mounting ring and lens adaptors).

You can add extra SB-R200 Speedlights, as David has done here – he usually works with five SBR200 flashes. “How many Speedlights I use depends on how large the subject is, and how close it is to the lens,” he explains. “I want light coming at my subject from all angles. If it’s very close to the lens, I need to pay special attention to making sure the light is getting to the underside of my subject.”

Configuration

Everything is configured within the camera itself. Switching over to focus stacking is fairly straightforward, but it’s worth checking your camera’s manual.

Start in the camera’s Focus Shift Shooting menu. From here you can adjust settings such as focus step width, number of shots and the interval between shots.

‘Focus step width’ controls how far the parts of the lens will move towards the subject. In these examples, David went with 3.

Next, you’ll need to choose how many shots you want the camera to take for your composite. David usually goes with anything from 50 to 125, depending on the size and depth of his subject.

The ‘interval until next shot’ setting dictates the time between shots, which is important because, as David explains, “You get through flashes very quickly and need to take this into account.” He sets this to 00 – the default setting for five shots per second.

All these settings will need to be tweaked depending on your subjects, their size and the NIKKOR lens you use.

Tips and tricks

Over the course of his career, David has compiled his own set of golden rules. Consider this your insider’s guide to weaving focus stacking magic.

Prep your equipment

- Make sure your camera’s battery is fully charged – you’re going to need at least 120 photos.

- Disable VR – you don’t need it with a tripod.

- Play around until you find what’s right for you but, for his focus stacking, David’s go-to settings are 1/60th of a second, f/8 and ISO 64.

Check your settings

Head over to the Focus Shift Shooting menu, and make sure ‘silent photography’ is disabled: flash won’t work if it’s on.

David suggests enabling the ‘exposure smoothing’ feature in the Focus Shift Shooting menu for softer, smoother exposure.

Focus settings are key. The D850’s focus shift mode is set to autofocus by default but, before David enables this mode, he sets the starting focal point manually, which is crucial to getting the best results.

Experiment with accessories

David fitted a magnifying eyepiece to his D850 to help him hone in on the finer details in the viewfinder. “I also zoom in on the LCD screen preview so I get ultra-sharp focus,” he says.

Monitor technology is so advanced nowadays that using 100% view on the monitor makes it incredibly easy to achieve incredibly focus accuracy.

Minimise movement

This is especially important when you’re shooting plants or flowers. Hot air rising in a room, air-conditioning kicking in or a breeze coming through the window are all enough to ruffle delicate petals and stems.

“An average session lasts around 15 minutes, and that whole time I’m thinking about how the air is moving, how I’m moving, whether my camera is shaking,” says David. “Flowers are living things, and living things move. Don’t forget that a flower starts wilting the moment you pick it. I take my photos in a darkroom, because flowers will turn towards even the faintest glimmer of light.”

To get them used to the dark, he transfers his flowers to a darkroom a half day or a full day before shooting, depending on the type of flower and how fragile it is. Research and experience will help you get to grips with how long different flowers need.

If you do end up with a little movement, don’t panic: this is where stacking software comes in. “It’s why I take up to 150 photos, sometimes more: I can cull the dud shots and end up with a result that works,” says David.

Find your distance

So generally how far are David’s subjects from the front of his lens? “They can be extremely close – a matter of inches, depending on the size of the flower – but not so close that they’re difficult to light up with flash,” he explains.

You’ll need to experiment, and embrace trial and error. “I take individual test photos to pinpoint how far the lens needs to be from the subject for the best lighting,” David continues. “Lighting is the single most important thing to play around with. Once I’ve got the lighting, I know the focusing will work. Lighting is the main challenge.”

Choose your location

Where you work makes all the difference. Ideally, you’ll be in a dark, quiet room such as David’s studio space (at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California), where he took the photos you see here. Take your time to get the conditions spot on.

Practise before you pitch

The quality of David’s work has paved the way for a long-standing relationship with the Huntington, which now supplies the plants he photographs. “Botanical gardens are good clients,” he says. “The Huntington has around a dozen of my photographs in its permanent collection, and many of those are on display. There are definitely opportunities for photographers who master this technique.”

He advises: “Buy some supermarket flowers and practise at home until you get quality proofs. Then reach out to botanical gardens. Many of them need people to shoot their collections. It’s a fantastic way in.”

And finally, think big

There’s more to focus stacking than plants. Experiment with eye-catching insects, butterflies, coins, stones, bark, jewellery, shells, rock formations – anything with intriguing structure and complex texture. Elevate the ordinary and turn the everyday into something special.

Uncover NIKKOR Lenses

Featured products

More in macro

Exploring abstract macro photography at home

For limitless creativity